Introduction

Philosophical –Ontological and Epistemological– Beliefs

Ontology pertains to the examination of fundamental principles of existence, whereas epistemology concerns the analysis of the link between knowledge and reality, including the potentialities and standards of correctness and authenticity of knowledge.The two terms–ontology and epistemology–are often discussed independently, although their relationship and unity emerge necessarily and dialectically, given the content they negotiate. The notion of ontology, which is more fundamental, has been specialized and adapted accordingly for social sciences research and has emerged as the premise embracing claims and assumptions about the nature of social reality and the individual elements and their interactions that create it

Responses to pertinent philosophical questions vary according to the school of thought and establish distinct theoretical orientations. The present discussion will concentrate on the two predominant philosophical orientations: the positivist approach and the constructivist stance that is associated with both hermeneutic and critical perspectives.

In classical positivism, the foundation of knowledge was believed to be located in empirical, sensible phenomena, and knowledge was formed using formal logic and incorporated into scientific laws. Logical positivism, as an extension of classical positivism, preserved the empiricist view that objects and relations of similarity and succession are ascertainable by sensory experience and empirical testing. It simultaneously indicated that the association between formal logic and scientific language can facilitate the formulation of objective observations. Language fulfills a representational role, as it is linked to the world by some defined function. A statement is meaningful and, therefore, scientific if and only if it is empirically verifiable. Rational predictions of future experiences can be attained by following the patterns of past experiences, as experience is the sole pathway to knowledge. Nonetheless, no assurance is offered; the possibility of error remains ever-present.In summary, the theorist is instructed to clearly define concepts functionally and conceptually, relate these concepts to systems of causal relations, and support theoretical premises through iterative scientific processes, serving the purpose of science, which is to observe and predict patterns of experience. Accordingly, this approach largely retained assumptions about the knowledge of social reality based on objective principles. Moreover, these assumptions encompass interdependent notions, such as the idea that knowledge can be best achieved by searching for regularities and causal relationships between the components of the social world. It is worth noting, however, that these regularities and causal relationships are rarely simplistic and often involve multiple factors and relationships of extended duration.

On the other hand, as mentioned above, the epistemological position of constructivism is closely related to hermeneutic and critical theory. Notwithstanding, beyond minor differences in philosophical considerations, a dominant common assumption can be identified that social reality is constructed through how individuals define and make sense of it and, by extension, through behavior and action in conditions of communication and interaction with other subjects. For Durkheim, preconceptions in human consciousness precede the actual social reality, and correspondingly, ideas precede their scientific foundation and often remain at this level of conception, lacking evidence and explanations. Language does not passively name objects but actively shapes and forms the world. Thus, reality is constructed through the interaction between language and aspects of an independent world. In this tradition, it is impossible to demonstrate causal relationships between phenomena sustained in space and time since social phenomena are not subject to the same observation as natural phenomena.

Understanding social phenomena requires an examination of how social subjects conceptualize them. It is worth noting at this point that the emphasis is on understanding rather than explanation, and relates to human justification and intentions as reasons for social action.In this perspective, understanding and interpretation encompass all the functions of the sciences of mind and include experience, continuous interaction, understanding manifestations of life and other people, but also of the self.

Knowledge has the characteristic of being culturally directed and historically situated, as it arises from specific situations and is not reducible to simplistic interpretation; hence, it is acquired inductively and proceeds to the development of theory. The hermeneutic tradition does not challenge ideologies but accepts them and has predominantly the aim to bring hidden social forces and structures to consciousness. Regarding the critical dimension of epistemology, the additional essential element is that knowledge is simultaneously identified as socially constructed and influenced by the power relations within society. What counts as knowledge is determined by the social and hierarchical power of the proponents of that knowledge. More specifically, it highlights the historical variability of knowledge, which changes along with the evolving roles, orientations, and positions of those who produce knowledge within the social division of labor. Knowledge is not only changing and developing over time as new data are discovered, but old concepts are also refined, and new conceptual frameworks emerge, and thus fundamental changes might occur as society evolves.

The above theoretical and conceptual diversity is reflected in methodological issues concerning empirical research. Although an exhaustive review is out of scope of this study, we highlight some contemporary practices in the field. In general terms, measurement strategies are followed that require various methods of data collection, structured tools, questionnaires, interviews, vignettes, and essays.

Most empirical studies focused on exploring a set of distinct epistemological beliefs and, therefore, used multi-item questionnaires to assess these beliefs with samples of students, pre-service educators, and in-service teachers. Instruments for such investigations, including certain epistemological dimensions, have been known for decades (e.g., Epistemological Questionnaire (EQ), Schommer (1990); Epistemological Beliefs Questionnaire (EBQ)..However, both instruments exhibited weaknesses in terms of reliability, as well as in explaining only a small proportion of the variance, raising validity issues. Other methods of investigating epistemological beliefs or epistemic cognition, as mentioned above, are classified according to the nature of the data, including vignettes, interviews, essays, concept maps, and so on. This renders a differentiated focus of research using semantic data, emphasizing a more exploratory perspective and understanding of the field in greater, perhaps, detail.

Although literature has highlighted the fundamental importance of ontological understanding /cognition, it has not been investigated or connected with personal epistemology. This is due to the drawbacks in measurement issues, although some attempts have been made to include ontological beliefs in empirical research (Greene et al., 2008). Empirical explorations of ontological beliefs have achieved a better connection of personal epistemology research with epistemology as a philosophical branch and, possibly, to an improvement in the conceptual structuring of the field.

Another aspect for discussion pertains to the extent to which epistemological beliefs or epistemic cognition are general or domain-specific in nature. The generality of beliefs entails the position that epistemological beliefs develop as general perspectives or understandings of the world, so that one’s beliefs regarding the origin and justification of knowledge are likely to be similar across different domains (Schraw, 2013).

However, current thinking in the field suggests that epistemic cognition has both general and domain-specific aspects. This perception appears to be true under the lens of complexity, where considering continuous interactions between top-down (domain generality) and bottom-up (domain specificity) processes.

The above highlights some of the concerns permeating the field and the inherent difficulty related to the very nature of personal epistemology that challenges researchers.

Considering the above, this study aims to investigate the philosophical, ontological, and epistemological perceptions that students form during their academic life. Note that ontological supposition crucially determines epistemological beliefs so that the answers to the two philosophical aspects do not usually contradict. That is, the position of subjective knowledge about reality does not descend from the realistic view. Given the different approaches to epistemological contemplations, students’ epistemological beliefs have been an intriguing field of inquiry because, as research has shown, they are related to many individual differences, playing a determinant role in academic life.

The above philosophical views, fostered by university students regarding the nature of reality and knowledge, are the objective of the present inquiry, which implements two methodologies to probe these internal structures.

Concept Maps as Representations of Mental Models

Human perceptions, knowledge, or beliefs, personal conceptualizations, and any latent variables, due to their complex structure, can be described as a web, where concepts, principles, and other types of conceptual elements are connected in a complex way, forming a knowledge/belief system. In short, the starting point and the development of concept maps are situated in the need for representing conceptual understanding, knowledge, and beliefs, thus providing an illustrative portrayal of an individual’s internal conceptual structure or mental model.

More generally, a mental model refers to small-scale constructs or representations of reality used to provide explanations and predictions. They are acquired through experience, formal and informal learning, and vary in terms of functionality and stability, while they have a subjective and idiosyncratic character, reflecting a personal understanding of the relationship between the parts of reality. There is an essential distinction between an image that is merely represented in the mind and a more complex, abstract, or conceptual archetype created through detailed understanding. A mental model is considered a relatively robust but limited internal conceptual representation of an external system whose edifice preserves the system’s perceived structure and relationships, while its dynamic character is one of the basic assumptions.

From the literature review, five main features of mental models emerge: mental models are internal representations; language is the key to understanding mental models, that is, they can be represented linguistically; in the cognitivestructure of an individual, the meaning of a concept is embedded in its relationships with other concepts; the meaning of a concept can be shaped by the individual’s interaction with his or her environment; and last, the mental model can be ontologically considered and represented as networks.

From the above features, the most crucial is the representation of the mental model as a web of concepts, or concept maps, because it is associated with the accessibility of these internal structures. In research, concept maps are considered the extracted visual portraits of the internal structures, often called inferred cognitions. Specifically, a concept map refers to a diagrammatic illustration consisting of node concepts linked to other nodes within the framework of a given theme. It reflects organized knowledge that could be visually depicted by the relationships between elements within a knowledge domain via semantic or meaning-driven links.

The semantic networks vary among experts and novices in terms of connectivity and strength. For example, scientists are expected to have complex, highly connected cognitive structures with deep, meaningful connections between concepts, while novices are presumed to have relatively disconnected and sparse cognitive structures with superficial, weak connections between concepts.

In semantic analysis, a concept can be a single theoretical category, which can be expressed in a single word, a nominal phrase, or even a verbal phrase; thus, a concept is an ideal, abstract core that is concretized in its association with other concepts. A relation, then, refers to the bond that connects two concepts, which, however, is not univocal; instead, it may express a conceptual relationship, or it may indicate that the concepts are somehow cognitively related in one’s mind, or it could be merely an expression of their proximity in a text. Concomitantly, the connections between concepts may possess directionality, akin to a force, sign, or specific meaning. Furthermore, the sign of a relationship can be distinguished by indicating either a positive or a negative relation, and of course, the relation between two concepts can differ in meaning.

Linguistically, a statement requires two concepts and the relationship between them. A map, which is a network of concepts, expresses many statements, while two statements are connected if they share a common concept. These primary considerations are significant when implementing semantic analysis on speech recorded as textual data. A map extracted from the encoding of a text created by an individual can be seen as a representation of the individual’s mental model. If two or more persons synthesize the text, the ensuing map represents the shared or group mental models. In conclusion, the semantic representations resulting from content analysis through natural language processing, with the contribution of network theory and other disciplines, reveal the cognitive structures and mental models underlying the original data, highlighting their complex structure and properties. In the present study, the first approach fosters this ontological representation, and students’ mental models are examined using concept maps. Within concept maps, the mental model is operationalized through three measurable dimensions: concept strength, reflecting the frequency or prominence of individual nodes; concept relevance, capturing the co-occurrence and connections between concepts; and conditional probability, indicating the likelihood of one concept appearing given another, which helps reveal stable, coherent patterns or relationships within students’ cognitive structures. Regarding coherence, this study focuses exclusively on semantic coherence within concept maps, assessing the logical organization and arrangement of concepts from primary to secondary ideas.

This paper builds upon the above framework to explore university students’ internal cognitive structures regarding their philosophical views on reality and knowledge.

Methodology

Objectives and Research Questions

The main objective of the present research is the in-depth study of the epistemological beliefs of students in faculties of education, contributing, so, to the field at a theoretical level regarding personal epistemologies and social representations. The other objective concerns a contribution at a methodological level.

Within the first objective, and towards establishing a better connection between personal epistemology as a psychological construct and philosophical epistemology, and focusing on the emerging dominant tendencies among social science students, the first research question posited is whether students’ epistemological beliefs can be conceptually integrated into one of the existing epistemological models (Research Question 1).

At the same time, acknowledging that every philosophical assumption, formal in the sense of systematization or perceived in the sense of a subjective, explicit, or implicit, is associated with a logical consistency between ontological and epistemological beliefs. Given that perceived ontology precedes, the second research question is whether in students’ minds the ontological) beliefs are associated with consistent epistemological) ones, or whether a multiplicity-co-construction of tendencies is observed (Research Question 2).

Returning to formal epistemology, in the social sciences and in the educational sciences in particular, the theoretical and methodological dimensions are largely influenced by the epistemological orientations adopted by researchers. The relatively rich literature is illuminating with respect to the variety of approaches and perspectives that exist within the social science community, the historical process of their emergence, as well as their deeper, explicit differences or commonalities. This paper focuses on the two general and dominant epistemological tendencies, namely, the epistemological positions of positivism and constructivism. These two epistemological “schools of thought” appear as the prevailing orientations in most methodology instruction books, together with a multitude of comparable variations and alternative philosophical positions. These lead to various research directions and, quite evidently, reveal that within the social sciences, a multiplicity of epistemological and methodological choices is offered to novice scholars. In the present inquiry, to reduce this complexity, we focus not only on positivism and constructivism, but also on any denial or departure from both. In the survey data analysis, it was examined under the code of skepticism, without necessarily referring to the corresponding formal epistemological school of thought. The essential question is whether students’ epistemological belief system is characterized by consistency regarding the prevailing epistemological positions, or by fragmentation (Research Question 3).

As mentioned above, the second objective of this paper concerns a methodological contribution. By applying different methodologies intended to promote an enriched approach of mixed methods that can provide and ensure enhanced reliability of the findings. It is expected that the two methods, as non-alternatives, will not provide an identical portrayal of the system under study, but in tandem, their analyses will complementarily provide enhanced interpretation and better understanding. Moreover, since the two approaches, semantic analysis and survey data analysis, have different philosophical origins, i.e., qualitative versus quantitative, the proposed application could initiate further discussion and reconsideration of integrative perspectives.

Participants

The research sample was selected in accordance with the research questions, acknowledging that the investigation of beliefs about the nature of knowledge required a degree of specialization more likely to be found in adult and, specifically, academic populations. Accordingly, data collection focused on postgraduate students in the Social and Human Sciences. This group was considered particularly relevant, as its members represented both the current and prospective teaching workforce of educational institutions, as well as future researchers in the wider field of education and the social sciences.

This study employed a convenience sample, selected primarily for reasons of availability and accessibility, which limits external validity and does not allow for full generalization of the findings to the broader population. Nevertheless, the sample also presents the above desirable characteristics, as it demonstrates a degree of specialization in the field of social sciences, enhancing the relevance and interpretive value of the results.

The qualitative part of the study comprised eighteen postgraduate students (seventeen women), who submitted two essays articulating their philosophical views on the nature of reality and knowledge. These essays (180 pages in total) formed the corpus for semantic analysis using Leximancer, aimed at generating collective concept maps and uncovering deeper conceptual structures surrounding the issues under study.

In addition, for the survey part, 120 postgraduate students (82,72% female, 17,28% male) from the same school completed the questionnaire used for the quantitative analysis.

Instruments and Procedures

The instrument chosen for collecting quantitative/computational data was selected on the basis of the following rationale. Given the ongoing debate regarding the nature of epistemological beliefs—whether they are general or domain-specific—and the contradictory results produced by internationally applied questionnaires focusing on general beliefs (EQ, EBQ, EBI)The present study adopted theNature of Science(NOS) model.

The theoretical construct of NOS, as expressed through the questionnaire, refers to the epistemology of science, science as a way of knowing, and the assumptions embedded in the development of scientific knowledge. In his revised work, further, it conceptualized scientific knowledge as tentative, empirically based, theory-laden, creative, and socio-culturally embedded—dimensions that were incorporated in the self-report Likert-scale questionnaire of 29 items developed by Cho et al. (2011).

An additional rationale for employing this instrument was its explicit integration of the socio-cultural dimension. The literature highlights the need to investigate the perceived role of socio-cultural factors in shaping epistemological beliefs, with an increasing number of studies examining personal epistemology in socio-cultural contexts. Since individuals are inevitably influenced by such factors, which shape their perception of the world, social reality, and epistemological issues (e.g., nature and justification of knowledge), including this dimension was considered essential.

For the purposes of this study, the NOS questionnaire was adapted. During adaptation, items related to the creative/imaginative dimension of scientific knowledge were excluded to avoid possible confusion among participants. The final instrument consisted of 29 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale. Six dimensions were examined: (1) the empirical and (2) tentative nature of scientific knowledge, (3–4) its subjective and objective aspects, (5) cultural influences, and (6) methodological perspectives. Some scholars have argued that such questionnaires may not fully capture the complexity of epistemic beliefs (Lederman et al., 2002). Open-ended questions, which allow participants to articulate and elaborate on their reasoning, may provide richer insights into complex epistemological constructs (Hofer, 2001); however, this approach presents challenges, such as the difficulty of coding large numbers of diverse responses.

In the present research, merely part of the NOS scale was used. The selection of items was based on the needs of the design, focusing on categorization positivistic/constructivist/skeptical. This transformation to a 3-item categorical scale facilitated the implementation of LCA and the response to research questions. Moreover, the common reliability coefficients are not applicable here, because the consistency of responses is what is investigated (Research Question 3).

For the second method, the semantic data collection took the form of essay writing, conducted over two weeks to ensure continuity and consistency. Participants were given one week per essay for reflection, revision, and writing. The instruction specified that the essays should contain at least 1,000 words. The assays aimed to address two open-ended questions: one regarding the ontological dimension (the perceived nature of reality), and the second focused on the justification of knowledge (how one distinguishes a claim from knowledge). These questions were intentionally phrased in abstract terms to capture students’ general beliefs without imposing the researcher’s own assumptions.

Data were gathered in the context of a university course on educational research methodology, chosen both for its thematic alignment and for its potential to strengthen the research process. Because the development of any methodological orientation presupposes epistemological assumptions—even when not explicitly recognized—this setting was deemed especially suitable. Students were instructed to formulate their own perspectives without consulting the literature, while the instructor’s role was restricted to clarifying unfamiliar terms, ensuring that responses remained authentic and uninfluenced.

The Leximancer Software Package

The Leximancer software package performs conceptual analysis of natural language textual data, modeled on content analysis using master concept classifiers. It is a software system that employs data mining techniques adopted from computational linguistics, network theory, machine learning, and information science.

It is suitable to process large and complex corpora of textual data quickly and provides direct visualization of core ideas in the form of concept maps, further facilitating interpretation and semantic analysis. The strategy for conceptual mapping the text involves extracting word families and utilizing concept thesauri to categorize the text through multi-sentence analysis. The resulting concept tags/encodings are registered to provide a document exploration environment for the user. They automatically identify entities named as concepts and themes by recording co-occurrences, which encompass the connectivity of each concept and the information for constructing the semantic network. Themes are clusters of concepts, which, like concepts, are heat-mapped, meaning that warm colors (red, orange) indicate the most relevant themes, and cool colors (blue, green) are the least relevant. The map visually represents the strength of the connection/relationships between concepts and provides a conceptual overview of the semantic structure of the data. Leximancer has three main advantages: Speed and rigor with a large block of data, and immediate visualization and interrelations. Although there is no single or precise way of analyzing data, Leximancer is designed to have a holistic perspective of themes, central ideas, and concepts to reduce the biases of manual content analysis based on preconceived criteria, leading to firm and reproducible results. Leximancer procedure provides a worthy cross-check. An interesting and perhaps the most critical aspect is that the present tool and the course of inductively revealing the essential elements of the system under study mimic or resemble the Grounded Theory process. This procedure has significant implications for methodology when unified frameworks are sought.

Cluster Analysis

The quantitative analysis used was a clustering method known as Latent Class Analysis (LCA), which is primarily designed for qualitative data; that is, the input is measured at the nominal level. The advantage of LCA is that limitations related to distributional assumptions, normality, or linearity do not hold. Note also that the independence assumption that constrains latent variable models does not affect the results in the present LCA application,testing the coherent vs fragmented hypothesis(Stamovlasis et al., 2013).

Based on conditional probabilities, the method is capable of classifying the cases into groups that have similar patterns of responses.In this way, the resulting classification reveals participants with consistent responses to the questionnaire or a coherent belief system. Coherency means that students’ philosophical beliefs adhere evidently and exclusively to a specific orientation, i.e., according to either the positivistic or the constructivist stance. In case students’ predominant orientation is, for example, positivism, and if this stance is coherent, then all responses would beconsistentwith this orientation. On the contrary, if the participants’ responses are inconsistent, the philosophical stance will not be coherent, but ratherfragmented. The consistency in a set of this kind of empirical data can be visualized as homogeneous clusters in a bar graph that have all responses in line with a specific philosophical orientation and with probabilities ofresponse close to unity. The specific use of. The quantitative analysis can be performed in R.

Findings / Results

Semantic Analysis with Leximancer

After the collection of the textual data, the files were prepared in line with the research questions. When the interest was not in potential individual differences, aggregated files containing the responses of all participants were used. Once the preparation of the files was completed, the analysis process began, comprising the following stages. It should be noted that these steps were applied to all essay topics, and the collected textual data were analyzed in the original language.

The first stage involved selecting documents and importing the required files or folders for analysis.

In the second stage, the so-called concept seeds were created. This stage included two components: text-processing settings and concept-seed settings. The first involved specifying the parameters for segmenting the text from which coding would be derived, while the second involved defining the criteria for identifying concepts, including their number and proportion.

The third stage involved the development of the thesaurus, which also consisted of two sub-processes. In the first option, users were provided the ability to revise, remove, or merge automatically recognized concepts. At this point, concepts could also be manually inserted by the researcher to be searched and identified. The second sub-process involved thesaurus settings that refined the earlier concept-seed choices. At this stage, articles, conjunctions, and other lexical items deemed semantically or conceptually uninformative could be removed. Moreover, concepts could be merged across singular and plural forms (e.g., science–sciences, subject–subjects). This procedure was regarded as essential for reducing “noise” in the data and for producing a meaningful representation of the concept map.

The fourth stage focused on settings related to the final output, namely the visualization of the concept map. During this stage, concepts to be included or excluded from the map were selected, and additional parameters were specified, such as the type of network and the size of the theme.

The textual data analyzed elaborated on beliefs and perceptions of reality (both objective and subjective) and the possibility of acquiring objective and valid knowledge. Moreover, some basic assumptions were made about the occurrence of specific concepts corresponding to each paradigm under study, namely positivist or constructivist. Thus, for the positivist approach, we assumed the existence of nature, experience, senses, laws, relations, phenomena, logic, research, methodology, reason, explanation, prediction, neutrality, and verification; for the constructivist approach: construction, intersubjectivity, experience, meaning, idea, language, contexts, action, interpretation, understanding, researcher, interaction, and engagement. Note that the above indicators for each paradigm concept do not encompass all possible ones, but rather represent the most anticipated and central to the philosophical orientation.

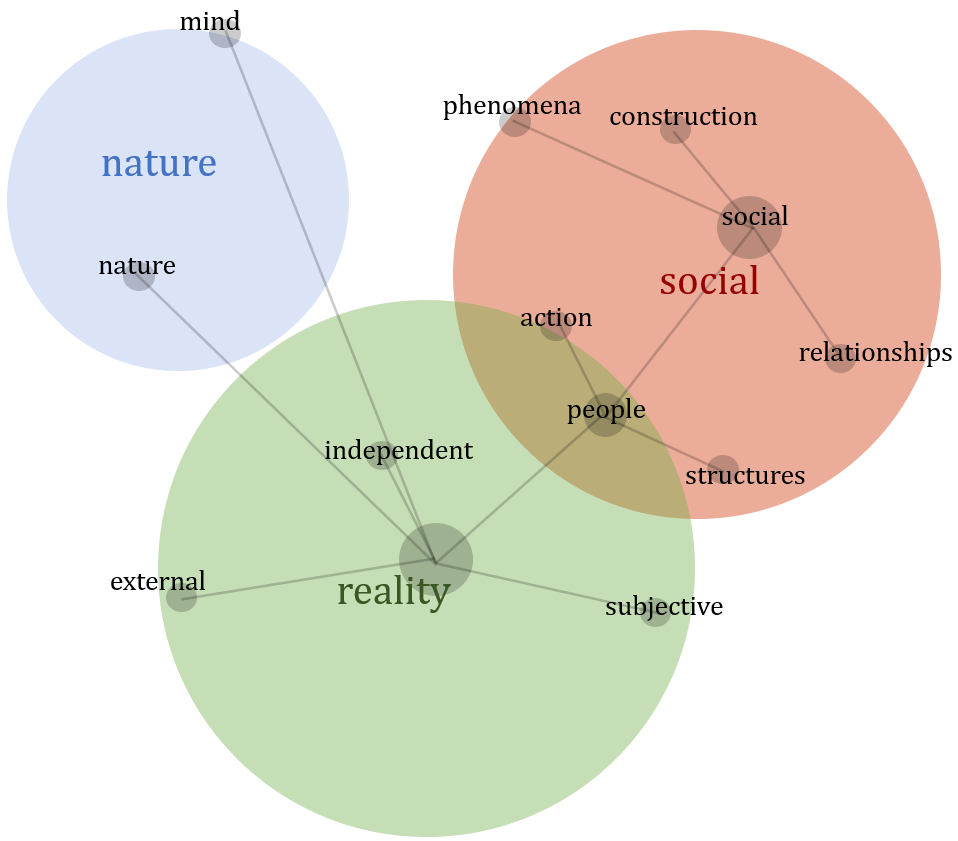

The processing of textual data, which elaborated on these philosophical/ontological questions about the nature of reality resulted in the collective concept map depicted in Figure 1. The analysis was performed on the original Greek texts. All outputs presented are translated into English.

Figure 1. Collective Concept Map from Essays on the Nature of Reality

The strong cluster designation, based on size and color, depends on the individual embedded concepts —i.e., the concepts co-identified by the central or localized relation from the context —and on the recurrence of the present concept. Three central themes emerge: reality, social, and nature. According to the criteria mentioned above, the strongest central theme is social, followed by reality and nature. The content of the partial themes provides an initial insight into the prevailing perceptions in the current collective concept map regarding the question under investigation, without overlooking any weaknesses. The concepts that constitute the first theme, apart from the central one (social), are the following: people, relationships, construction, phenomena, action, and structures. The second theme (reality) consists of subjective, independent, and external concepts. While the third (nature) and weaker one includes only itself and the mind.

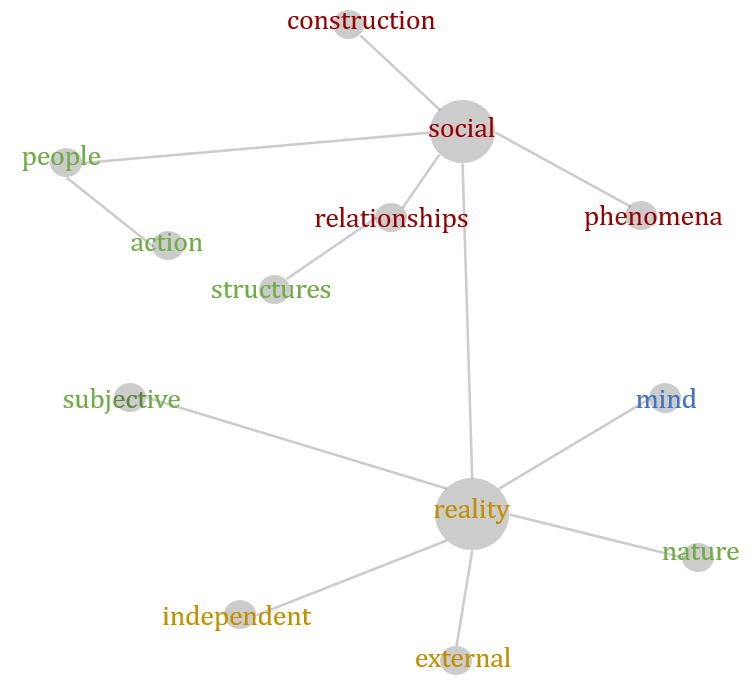

Figure 2.Cloud View from Essays on the Nature of Reality

Table 1 presents the emergent central themes and co-occurring concepts used to extract the concept map for the ontological question about reality. Considering the concepts that emerged (Figure 1), it is apparent that a constructivist tendency is present in the students’ formed perceptions, at least at the ontological level, as concepts dominant in the constructivist ontological view are present and recognized, with construction and subjectivity being the most characteristic ones. Indeed, it cannot be disregarded that, despite the predominance of constructivist-related concepts, some of the positivist orientations, such as external, independent, and nature, but not objective, can also be found. These concepts relate only to the concept of reality, a fact that suggests a possible distinction between nature and reality, attributed to the characteristics of being external and independent of the human subject, as opposed to social reality, which is a product of construction and human relationships. However, such a notion does not contradict the core of the ontological view of constructivism, especially since concrete characteristics do not define social reality.

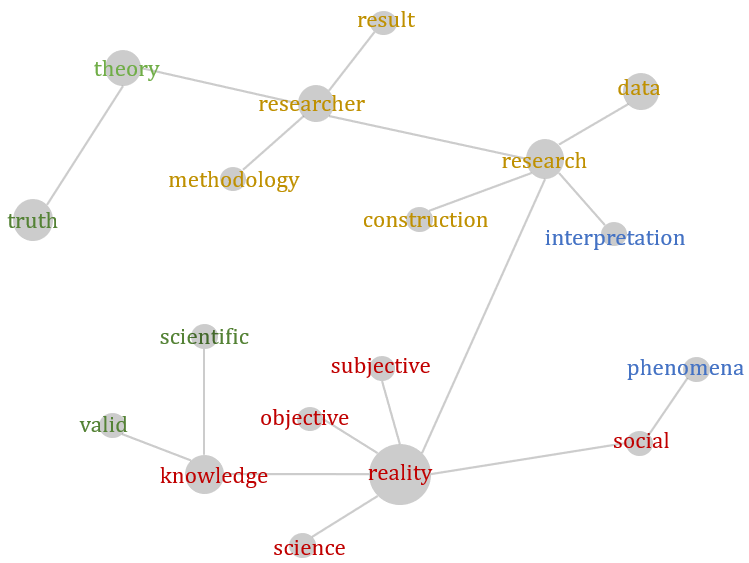

Another feature presented here, in addition to concept maps, is concept clouds(Figures 2 and 4), which represent the most frequent and relevant concepts extracted from the data. As in concept maps, the most relevant concepts are depicted in warm colors (red, orange) and the less relevant concepts in cooler colors (blue, green), while the size of the node/concept corresponds to the frequency of that concept, and the relevance between two or more concepts is determined by the distance between them. Nevertheless, concepts are not organized into themes, unlike concept maps, but more closely resemble a network in the case of concept clouds.

Table1.Emergent Central Themes and Co-Occurring Concepts Shaping the Ontological Concept Map of Reality.

| Main Theme and frequency of occurrence | Concepts | Relevance | Coexistence of the 1st concept with other concepts (in parentheses, Estimation of the conditional probability) | |

| reality (182) | realitysubjective independentexternal | 100%46%5%6% | social (100%)relationships (100%) nature (100%)phenomena (100%)mind (100%)ideas (100%)subjective (99%) | objective (96%) action (94%)people (90%)construction (90%)structures (89%)external (79%)independent (60%) |

| social (126) | socialpeoplerelationshipsconstruction phenomena actionstructures | 100%73%24%23%15%13%3% | relationships (100%)construction (100%)subjective (88%)action (78%) | phenomena (73%) people (72%)structures (67%)reality (64%)mind (63%) |

| nature (20) | naturemind | 37%29% | external (75%)phenomena (72%)mind (72%) | reality (25%) relationships (22%)independent (21%) |

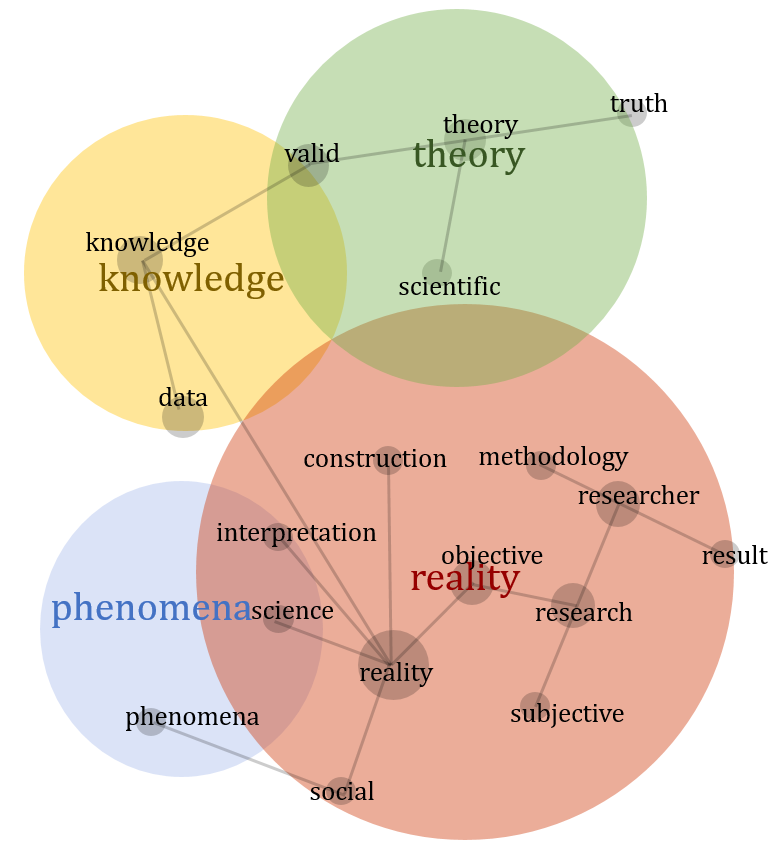

Processing of the textual data elaborating philosophical/epistemological questions about the nature of knowledge and the possibility of acquiring valid knowledge resulted in the following collective concept map:

Figure 3. Collective Concept Map from Essays on Knowledge and the Possibility of Valid Attainment

Figure4. Cloud View from Essays on Knowledge and the Possibility of Valid Attainment

Figure 3 illustrates the collective concept map that emerged from analyzing the essays that elaborate on the epistemological question of the nature of knowledge and the possibility of attaining valid knowledge. The appraisal is made in conjunction with Table 2, which presents the emergent central themes and co-occurred concepts on which the extracted concept map for the epistemological question about knowledge validity through research was based.

Table 2. Emergent Central Themes and Co-Occurring Concepts Shaping the Epistemological Concept Map of Knowledge Validity Through Research.

| Main Theme and frequency of occurrence | Concepts | Relevance | Coexistence of the 1st concept with other concepts (in parentheses, Estimation of the conditional probability) | |

| reality (267) | reality researchers research objective subjective social result methodology science | 100%89%40%33%27%20%18%15%12% | objective (98%) subjective (96%) interpretation (89%) social (78%) construction (75%) science (49%) | methodology (46%) researcher (33%)scientific (30%)research (27%) |

| knowledge (120) | knowledge validscientifictruth | 78%44%35%28% | valid (80%) scientific (75%)science (63%)objective (57%) reality (54%) methodology (53%) theory (47%) researcher (45%) phenomena (42%) | data (39%) interpretation (38%)construction (38%) subjective (25%) social (24%) research (20%)result (20%) |

| theory (112) | theorydataconstruction | 25%24%22% | researcher (89%) knowledge (78%) scientific (78%) construction (75%) valid (63%) truth (50%) methodology (47%) | result (45%) reality (44%) science (44%) research (30%) data (20%) interpretation (18%) |

| phenomena (38) | phenomena interpretation | 20%18% | social (35%) interpretation (29%) research (29%) data (28%) knowledge (25%)construction (24%) | reality (22%) researcher (20%) science (20%) objective (19%) theory (17%) methodology (16%) |

In these essays, the content of the discussion requires a clear transition from ontology to epistemology and consideration of the process (methodology); thus, it becomes more complex, and additional aspects need to be included in the concept map. In this collective concept map, four central themes(Table 2, Figure 3)are formed and presented in descending order of strength:reality,knowledge,theory, andphenomena. The first and strongest theme, “reality,” is composed, apart from itself, of the following concepts: researcher, research, objective, subjective, social, result, methodology, and science. The directly following strong central theme, “knowledge,” consists of the concepts of validity, science, and truth, while the third theme, “theory,” consists of data and construction. Finally, the theme “phenomena,” apart from itself, includes the concept of interpretation.

The concept map of epistemological issues (see Figures 3 and 4) appears more complex; however, compared to the former case (Figures 1 and 2), the conception adopted seems altered and more challenging to distinguish. While in the previous concept map, the concept “objective” was absent, in the present one, it appears closer to “reality” than “subjective.” Nevertheless, the concepts of “construction” and “interpretation” seem closely related to “research,” while the concept of “researcher” is placed at a central point in the network, establishing relations with “methodology” as well as with “results” and “theory.” Therefore, it seems that, in the perceptions under investigation, the subject researcher plays a crucial role in forming scientific knowledge.

An interesting observation is that a subject-object dichotomy emerges, which defines the concept of reality. It is evident that the core of this dichotomy is largely structured around the ontological opposition of objectivism and subjectivism, which has traversed the history of epistemology at least since the 17th century, transferring the dilemma to the level of cognition and knowledge: whether cognition deals with a reality that exists independently of it or with the events of its own consciousness. Expressions of these contemporary directions include both radical and social constructivism, in the sense that they ground knowledge in the experience—direct or indirect—of those who are considered to produce or challenge knowledge. They have likely influenced collective perceptions through formal and informal curricula, corresponding textbooks, and so forth.

To summarize, by extending the analyses to text that detailed epistemological questions about the nature of knowledge, the pure constructivist picture in this emergent concept map becomes less clear, possibly due to the more complex thinking required when epistemological and methodological issues need to be included, which might not be plainly understood or consciously elaborated. An additional explanation is that since the concept map under examination is a collective network of meaning and reflects an overall picture, the participants might not be homogeneous in terms of their mental representations and might not all be adhered to the specific paradigm. The remarkable findings of this semantic analysis need further investigation to enhance trustworthiness.

Cluster Analysis via Latent Class Analysis

This section reports the findings of clustering method applied to empirical data collected via the questionnaire. The participants responded to nine questions, with choices/answers: 1-disagree, 2-skeptical, and 3-agree; that is, a categorical marking scheme, which, depending on the question, classifies the response to the positivistic or constructivist stance or a skeptical position. For example, in response to the item “Research results are affected by the researcher’s personal beliefs,” mark 3-agree denotes a constructivist stance; in response to the item “Scientists make objective observations,” mark 3-agree denotes a positivistic stance.

In total, the items included in the LCA are:

Q1. Research results are affected by the researcher’s personal beliefs.

Q2. Scientists make objective observations.

Q3. The interpretation of the research findings depends on the researcher.

Q4. Science research does not lead to the truth because the truth differs for each person.

Q5. Scientific knowledge is objective and the same in all cultural environments.

Q6. Research results cannot be based on personal beliefs.

Q7. Scientists make objective observations that are not influenced by other factors.

Q8. Different cultural groups have different ways to attain knowledge.

Q9.Something that has been thoroughly investigated and scientifically proven is no longer a matter of change.

These items were selected to determine if, among the potential different groups of students, a specific philosophical orientation prevails, or if coherence of students’ philosophical beliefs is observed.

The clustering procedure identifies groups of response patterns with the same or similar set of probabilities of responses: positivistic/constructivist/skeptical. If the hypothesized latent categories are coherent, i.e., adhere to one merely philosophical orientation, students’ responses will be consistent in all questions. It is noted that the classification as a ‘skeptical’ view conventionally reflects a neutral or ambiguous position concerning the other two views, i.e., it does not necessarily correspond to a position of epistemological skepticism.

Among the different solutions, we chose the 2-cluster model on the basis of number criteria, such as the lowest BIC value,p-value (should be statistically insignificant), the smallest classification error, the largest Entropy R2and parsimony (the fewest number of parameters) (BIC=2225.5,Npar=37, Class. Err.=.0258,p=.10, EntropyR2=.85), as depicted on Table 3. Moreover, for our decision, we strongly considered class separation, sample size, cluster prevalence, and theoretical interpretability while evaluating the distinct response patterns in the generated profiles, as the theoretical interpretability of the model is crucial for making decisions among similar solutions.

Table 3. Class Enumeration Criteria.

| LL | BIC (LL) | AIC (LL) | AIC3 (LL) | N par | L² | df | Max. BVR | VLMR | p- value | Class. Err. | Entropy R² | |

| 1-Cluster | -1046.15 | 2178.479 | 2128.304 | 2146.304 | 18 | 962.714 | 102 | 4.361 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 2-Cluster | -1024.17 | 2225.473 | 2122.336 | 2159.336 | 37 | 918.746 | 83 | 2.885 | 43.9682 | .10 | .0258 | .8546 |

| 3-Cluster | -999.667 | 2267.434 | 2111.334 | 2167.334 | 56 | 869.745 | 64 | 4.608 | 49.0015 | .03 | .0547 | .8348 |

| 4-Cluster | -980.602 | 2320.265 | 2111.203 | 2186.203 | 75 | 831.613 | 45 | 2.831 | 38.1312 | .01 | .0963 | .8221 |

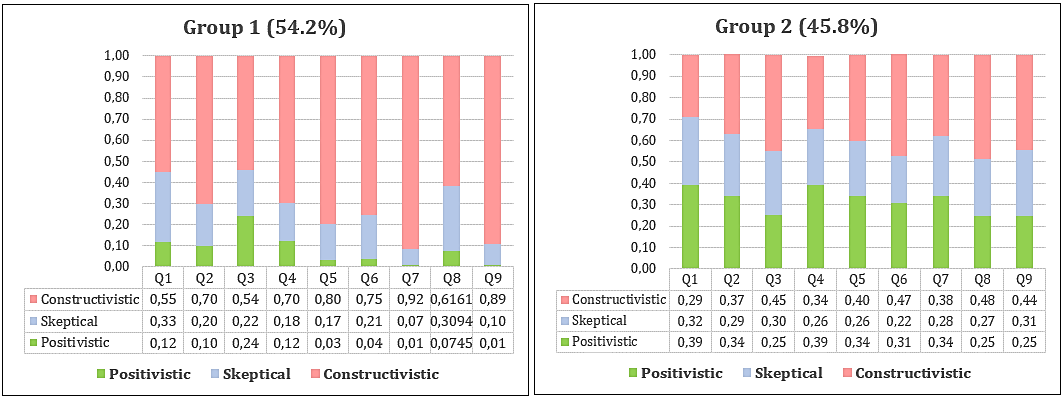

This anticipated consistency can be observed and evaluated in graphs of cumulative conditional probabilities. As established, two distinct groups of students emerged (Figure 5). Group 1 (54.2%) adheres to aconstructiviststance, as indicated by the corresponding gray color, which denotes a homogeneous set of responses. On the contrary, Group 2 (45.8%) appears heterogeneous and fragmented, with inconsistent responses. The results demonstrate that a large segment of the participants fosters the constructivist stance, while a smaller segment demonstrates inconsistency, showing that students have not fostered any of the philosophical orientations in question.

Figure5. Group 1 displays a coherent philosophical stance, whereas Group 2 shows fragmented and inconsistent responses.

Discussion

This research probed students’ philosophical, ontological, and epistemological beliefs about reality and knowledge by implementing two different methods. The first was based on a semantic analysis of textual data, aided by Leximancer software, which revealed the core mental representations as a concept map. The conceptual maps derived from the computer-aided content analysis represent the core and influential concept web that dominates students’ belief systems. These concepts, which are interconnected, comprise a network of meanings, and for the present data, they reflect certain philosophical positions that adhere to the constructivist orientation. In addition, a different quantitative approach based on cluster analysis was applied to identify the potential group of participants that follows the dominant philosophical trend. The hypothetical mental representations that dominated the philosophical belief system are sought as coherent mental models via the consistency of response patterns. Cluster analysis led to the same conclusion that students possess a constructivist stance. The findings from the present endeavor demonstrate the added value of a mixed-method approach, implementing different types of data sets and analytic methods. Although the two methods have qualitative and quantitative origins, respectively, they share similar characteristics adhering to grounded theory since the concept maps and the coherent group entities emerge inductively from the data and the analytics processes. This combination of methods, since different sources of data were used, can be considered as a triangulating approach, where the implementation of the two procedures in tandem adds rigor and enhances the reliability of the results.

The first research question, which this study posed and attempted to answer—and which cannot be viewed in separation from the other two—concerned the possibility of conceptually situating collective epistemological conceptions within a systematic epistemological framework, and more specifically whether there is potential correspondence with one of the most definitive research paradigms in the Social Sciences, both at the epistemological and methodological level, such as positivism or constructivism. To address these questions, the collective conceptual maps regarding reality and the possibility of acquiring valid knowledge were examined, as well as the latent classes, as derived from the respective analyses.

What was achieved through the investigation of the questions was the emergence and extraction of certain distinct epistemological dimensions, which agree with the existing literature. More specifically, the combination of the two methodological approaches highlighted empirical grounding, theoretical foundation, social and cultural integration, scientific methodology, temporality/variability, and subjectivity. These observations, however, are insufficient to accurately evaluate, let alone classify, the epistemological conceptions under investigation within any of the existing epistemological frameworks. Although semantic analysis provided a deeper perspective on those dimensions that exert the most decisive influence on epistemological conceptions, as a networked system—such as the cultural, empirical, methodological, etc.—it did not offer the possibility of further evaluation without risking arbitrariness, despite previous studies indicating the prevalence of one or another epistemological framework, while also highlighting the difficulty of approaching the various frameworks as points along a continuum, as if following a linear path. Currently, it is widely accepted that even contradictory conceptual elements can coexist within human cognition, a result of its inherent complexity.

Regarding the third research question, which sought to explore the possible logical and conceptual consistency between ontological views of the world and social reality and their corresponding epistemological perspectives, as well as the coherence of epistemological beliefs, the collective conceptual map represented by the essays on the nature of social reality and the results of the LCA were evaluated conceptually.

Thus, it may be assumed that students’ collective ontological conceptions, at a conceptual level, align more with a constructivist ontological approach to reality. More specifically, it is noteworthy that concepts prevailing in the ontological approach of constructivism, such as “action”, “social interaction”, “human relationships”, etc., are distinct. Of course, one could argue that these are neither exclusive to nor solely acknowledged within the aforementioned framework. Nevertheless, a sociocultural perspective more accurately emerges in the ontological views of the participants.

Therefore, taking into account the epistemological dimensions as they emerged both from the conceptual maps and from the results of the LCA (empirical grounding, theoretical foundation, social and cultural integration, scientific methodology, temporariness and variability, and subjectivity), it can be concluded that there is a conceptual continuity between the collective ontological and epistemological conceptions, without this necessarily implying their clear classification into any specific framework.

The finding regarding the constructivist orientation, which appears dominant and coherent in a large segment of the data, informs the relevant field and suggests that the majority of students are aware of the epistemological considerations. Furthermore, students recognize the tentative nature of knowledge supported by culturally situated perceptions and beliefs, a finding with implications for philosophical discussions in social sciences inquiries and concerns, primarily teaching research methodologies at the university level. The semantic network analysis which concepts-nodes are important and can suggest where potential interventions should be targeted to achieve conceptual change.

This endeavor tested the applicability of a combined approach that integrates various tools to establish reliable findings and contribute to a broader, mixed-methodological framework.More specifically, the study sought to highlight the particular opportunities for in-depth exploration that arise from the combination of different datasets as well as diverse analytical techniques. The two methods are different in many ways and operate under different assumptions of the reality under investigation. LCA considers the belief system as a latent variable responsible for the participants’ answers, while the semantic analysis considers the belief system as an associative network of meaning. However, we consider that the essential aspect is not limited to their comparison but is primarily found in the dynamic perspective emerging from the integration of quantitative and qualitative methods. Their contributions are in a way, complementary, and the combined implementation strengthens what has been learned, given the converging conclusions. Thus, the integration of methodologies is deemed essential and appears as an expected development, offering the potential to strengthen the unification of the methodological field by incorporating both qualitative and quantitative dimensions.

It is essential to mention that advances in digital technology and the software available merely provide speed and the opportunity to treat vast amounts of data. They should not be considered as replacements for the investigator, but rather as tools serving the researcher, whose role remains crucial and decisive. Programs, such as Leximancer, serve as assistants in the coding process, making associations and summarizing a cumulative portrayal of the data; however, they do not perform the analysis on behalf of the researcher. The same holds for cluster analysis, which restricts the findings to the researchers’ choices regarding the coding system, which must strictly reflect the guiding research questions.

The evidence emerging from the analyses is of considerable significance, as the sample represents both the future teaching workforce that will staff educational institutions and the future scientific capital in the broader fields of educational and social research. The interpretation of these findings is inherently complex, given the multifactorial nature of the phenomenon, and thus necessitates further and more nuanced investigation. Several scholars, viewing epistemological beliefs as the product of both informal and formal educational experiences (Anderson, 1984), emphasize the central role played by two interrelated cultural dimensions: the culture embedded within educational processes and the broader cultural environment outside them. Together, these cultural contexts contribute decisively to the formation of individual epistemological conceptions.

Moreover, given that curricula, teaching practices and textbooks at both school and university levels are, to a large extent, organized along common directions and content—frequently under a constructivist orientation—students’ epistemological orientations may be traced not only to the effectiveness of these curricular structures but also to the diverse cultural influences at play. Extending this line of inquiry, it becomes critical to examine the degree to which formal education, informed by constructivist principles, successfully distinguishes between everyday concepts—which may foster beliefs that, although containing elements of truth, lack scientific rigor and are deeply embedded in cultural frameworks—and systematically cultivated scientific concepts, whose goal is to promote rigorous methods of thought and understanding. Thus, a central objective of formal education is to facilitate the emergence of higher-order cognitive and psychological functions through intentional scientific intervention that extends beyond students’ pre-existing frameworks. Equally essential is empowering learners with the intellectual tools and reasoning skills necessary to critically evaluate—and, when warranted, reject—even deeply entrenched beliefs.

Furthermore, the epistemological, conceptual, and methodological pluralism inherent in Social and Educational Sciences—often infused with constructivist influences—inevitably permeates academic settings through curricula, textbooks, and the differing epistemological frameworks adopted by instructor-researchers. While such plurality enriches the academic environment, it may also generate confusion among students confronted with competing paradigms.

Conclusion

The present endeavor examined students' ontological and epistemological ideas through a mixed-methods approach. Semantic network analysis utilizing Leximancer software uncovered conceptual maps that illustrate university students ' belief systems, signifying a prevailing constructivist stance. The prevailing constructivist perspective indicates that several students acknowledge the culturally situated and provisional character of knowledge, an understanding crucial for research education and philosophical discussion in the social sciences.

Concurrently, cluster analysis validated belief patterns consistent with constructivist thought, indicating the presence of participant groups with common philosophical viewpoints. The synthesis of results from qualitative and quantitative investigations underscores the significance of methodological triangulation. Despite their distinct origins, both methodologies employ inductive reasoning aligned with grounded theory, ergo, augmenting the dependability and profundity of the findings.

This study emphasizes that although digital tools such as Leximancer and clustering methods facilitate data processing, the responsibility of interpretation lies with the researcher. Such technologies assist, but do not replace, analytical judgment. Finally, it has been demonstrated that the integration of varied approaches facilitates the advancement of mixed methodological frameworks, enhances educational research that promotes understanding and theory development in social contexts.

Recommendations

Since this work has a methodological dimension demonstrating the applicability of two different approaches, the first recommendation to educational research is to focus on the triangulation of methods, which guarantees enhanced validity. It is of paramount importance to implement digital technology tools, which offer additional advantages in terms of speed, data volume, and reliability. Regarding computer-aided network semantic analysis, it is strongly recommended for qualitative research to couple it with traditional content analysis. Future research might associate epistemological stances with independent variables, such as socio-economic background, gender, or educational level. Moreover, one could investigate students’ views of reality and the nature of knowledge, including additional aspects of their personal epistemology, while this mixed-method application can be further extended to any belief system in a social and educational context.

More specifically, academic experiences can influence students’ beliefs; therefore, the relationship between the academic context and epistemological beliefs warrants further exploration. Given that these students are prospective teachers whose epistemological beliefs may be reflected in their future teaching, the academic community should provide learning environments that help students develop more sophisticated epistemological views. Consequently, teacher educators need a better understanding of the types of epistemological beliefs held by pre-service teachers and how these beliefs change and develop.

Limitations

This research has certain limitations, originating from both approaches, including the use of opportunistic sampling in the survey and the collection of textual data. The participants were from a particular university, while no differentiation was made based on socio-economic background, gender, or other demographic variables. Restrictions are also imposed by the code systems, which are researchers’ choices, and the exploratory nature of this endeavor, which limitsgenerabilityand the final conclusions. Potential restrictions might originate from the software selection, given the numerous choices that digital technology offers. Additionally, the specific philosophical belief system has not been thoroughly investigated, as further epistemological stances may be relevant.

Furthermore, other limitations arise from the difficulty and complexity of the subject itself. That is, epistemological beliefs and personal epistemology comprise a vague area, where people internalize even the basic concept, such as objectivity, and this might be due to educational deficiencies and to the influence of the multiplicity of societal and individual factors. Nevertheless, the design and implementation of mixed, combined, and synthetic research approaches have become a required asset to face this challenge.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, which provides all the needed recommendations for carrying out research with adults. The study has been approved by the Ethics and Deontology Committee of the corresponding university (No. 280526/2021). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Generative AI Statement

In this work, no generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools were used in the data analysis, writing, or editing of this manuscript. All content is the original work of the authors. Where software tools were used for data management or formatting, these were standard, non-generative tools.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Gkevrou: concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, drafting manuscript, critical revision of manuscript, statistical analysis, securing funding, technical or material support, final approval.Vaiopoulou: concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, drafting manuscript, critical revision of manuscript, statistical analysis, admin, final approval. Stavropoulou: concept and design, data acquisition, data analysis/interpretation, drafting manuscript, critical revision of manuscript, statistical analysis, final approval.